Discovering Palenque: Mexico’s Lost City

The path narrowed as it wound through the undergrowth, skirting tangled roots and tracing the course of slender Mexican jungle streams. The heat and the humidity were energy-sapping, but I pressed on, snatching lungfuls of heavy, wet air and wiping the emulsion of sweat and suncream from my brow. Above was an unbroken canopy of cedar, mahogany, and young ceiba trees, their trunks studded with thorns as thick as my thumb. Strange birds with haunting calls moved in the branches and all around, cicadas screamed, winding themselves up like alarm clocks and hammering out urgent messages in shrill morse code. The path turned sharply. Webs of pearlescent spider’s silk hung across it in drifts, slung from the bushes and the emerald fronds of ferns. No-one else had been this way for some time.

There are thousands of Mayan ruins in Central America, but few have the charm of Palenque, a jungle-swathed city and UNESCO World Heritage site in southern Mexico, close to the border with Guatemala. This was once the seat of a great Mayan kingdom, a city state which flourished for a thousand years, from ca. 226 BC to ca. AD 799, before its rulers overstretched themselves, its farmers exhausted the soil and its great temples and pyramids were abandoned to the encroaching forest.

It was rediscovered by Spanish explorers in the 18th century and since then more has been written about its history and archaeology than almost any other Mayan site. Walking across the central plaza in the glare of the early morning sun – past the perfectly-proportioned pyramids with their elaborate roof combs and the palace with its many-tiered tower, from which Mayan priests would have observed the heavens – you’re struck by the flamboyance of it all. Nowhere better illustrates the architectural genius and flair of this great civilisation. It’s staggering to think that they did it all with nothing but stone chisels and bent backs.

I sat and ate a mango from my rucksack beneath the shade of a sapodilla tree and tried to imagine what it must have been like at the height of the city’s power: when the temples still had their coverings of stucco plaster, painted a brilliant red; when the aqueduct still carried water from the nearby River Otulum to feed the saunas and bathhouses of the palace; and when the ball court still drew crowds of spectators.

By all accounts the Juego de Pelota (the ballgame) was a brutal match, played by two teams using a 4kg rubber ball which they struck with their hips. According to the Spanish chronicler Diego Durán, players could be killed if they were hit in the stomach or the head and often received bruises so severe they had to be lanced open. Losing captains were also routinely sacrificed to the gods, which must have added a further frisson of excitement. Perhaps that’s why modern-day Latinos take their football so seriously. They’re used to playing with a lot at stake.

It’s not just Palenque’s architecture that sets it apart though. The city has also given us a wealth of carvings and inscriptions, which make the breathless climb to the top of every temple emphatically worth the effort. This is the kind of site that brings out the completist in you. I wanted to see everything and I sweated my way up flight after flight of limestone steps to watch the faces of long-dead kings emerge from the aging plasterwork. It takes a while for your eyes to adjust, but then the details begin to reveal themselves, like pages from some ancient Magic Eye – all Mayan world trees, jaguar pelts and quetzal feather headdresses.

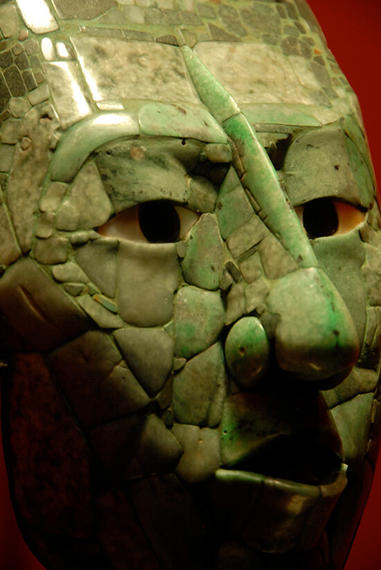

It’s because of carvings like these that we know so much about Palenque and trowel-clutching, Birkenstock-clad archaeologists have been able to piece together a complete ruling dynasty for the city, which began with the reign of the wonderfully-named Quetzal Jaguar (K'uk' Bahlam) around 431 AD. We know about the sticky, jungle war that simmered between Palenque and the neighbouring states of Calakmul and Toniná, and about Pakal the Great (603 – 683 AD), whose lavish tomb was discovered buried deep in the Temple of the Inscriptions. It was Pakal who oversaw the construction of many Palenque’s most magnificent buildings and who lifted it to the height of its prosperity. He was found lying in a vast stone sarcophagus, dressed in a funerary mask and a suit made of jade mosaic and gold wire. Hundreds of images were carved onto the surface of the stone, including one of the King himself, in the guise of the young maize god, escaping the jaws of the underworld to emerge reborn.

The chirping of the cicadas had reached fever pitch and somewhere in the surrounding forest a troop of howler monkeys began calling from their treetop perch, roaring like asthmatic lions. They’re a reminder of the most staggering fact of all about Palenque: only 10% of the site has been excavated. Cross the manicured lawns of the plaza and the river beyond and you’re in the city’s ancient suburbs, among crumbling stone residences, their walls thick with ferns and succulent jungle mosses. Beyond that, who knows. Palenque is no longer a lost city, but isn’t quite found either. It’s thought that there at least 1,000 structures still out there, hidden beneath the trees.

It was then that I saw the path snaking away into the undergrowth and I couldn’t help but follow it, breaking the skeins of spider’s silk and catching my shirt on the thorns of the ceiba to emerge in a boulder-strewn clearing. In front of me was a great mound of earth. Saplings and thick plaits of vine obscured its outline, but there was no mistaking what it was. Steps punched through the leaf litter like stone knuckles. A temple.

I scrambled to the top. An ochre-skinned lizard wriggled through a gap in the crumbling mortar. In the distance the howlers had started up again, sucking in croaky gulps of air and wheezing like punctured bagpipes. A blunt-edged pick axe was propped up beside a tree. Two stone slabs had been rolled away and beside them was a rectangle of black just a few feet across. The earth smelt of dark chocolate, loam and toasted maize. Is this what Alberto Ruz Lhuillier felt like when he discovered the tomb of Pakal? I slid onto my stomach, pulled a torch from my rucksack and peered inside.

Visit Palenque on our Best of Mexico Journey, which also takes you through Mexico City, Oaxaca, Tehuantepec, Merida and Playa del Carmen.